Black History Month Feature: Robert Blackwell and Interracial Cooperation

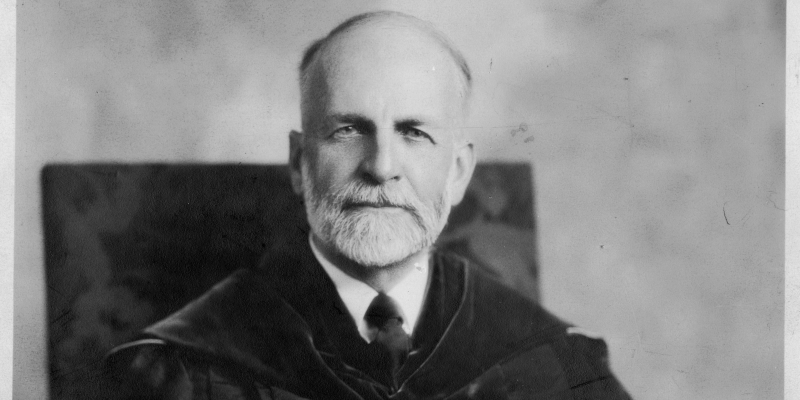

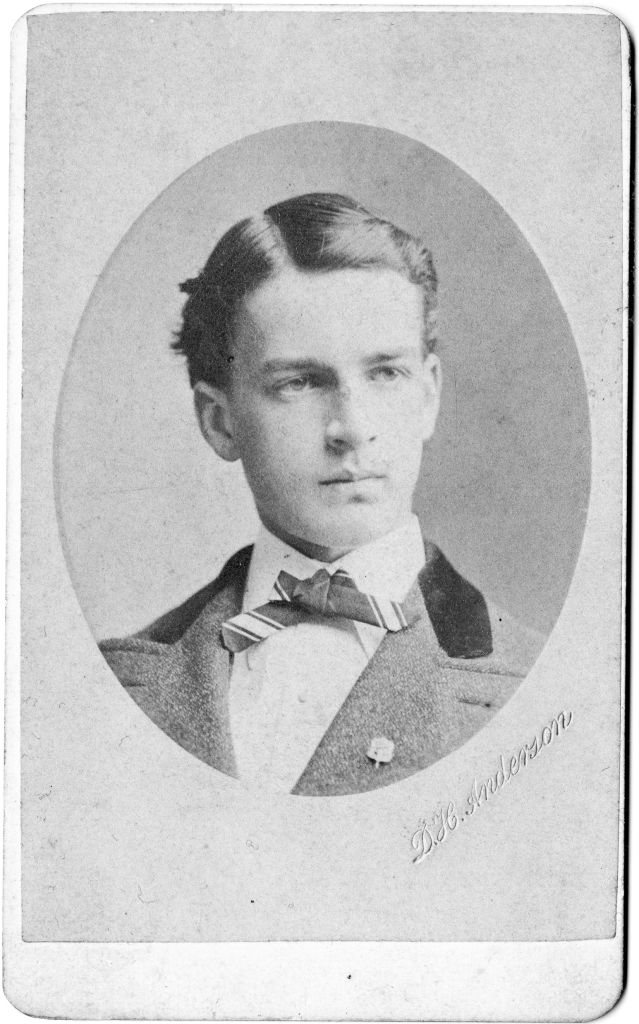

Robert Emory Blackwell was a boy of thirteen when he arrived at Randolph-Macon College in 1868. He was among the first students to attend RMC in Ashland, where the College had relocated after the Civil War from its original location in Boydton, Virginia. Young Blackwell had strong connections to the College as his father, John Davenport Blackwell, was vice president of the College’s Board of Trustees. Robert Blackwell distinguished himself as pitcher and captain of the baseball team, was a member of the Kappa Alpha fraternity, and received the Walton Greek Prize. After graduating from RMC in 1874, Robert Blackwell studied at the University of Leipzig, Germany. In 1876 he returned to RMC as a professor of English and Modern Languages and continued teaching even after his elevation to President of the College in 1902.

The early years of Blackwell’s presidency coincided with the stark increase in oppressive Jim Crow laws throughout the South. Virginia ratified a new constitution in 1902 which disenfranchised most Black citizens and codified segregation in the Commonwealth. After the disruption of World War I, life in the South did not “return to normalcy,” but entered a period of tension and turmoil caused by the rise of lynchings and the revival of the Ku Klux Klan.

American soldiers returning from the Great War in Europe encountered a home front very different from the unified, jubilant crowds which had cheered their departure in 1917. Racial tensions, job competition, and virulent anti-communist propaganda contributed to the violence of the “Red Summer” of 1919. In Virginia, Black war veterans were attacked during a celebration in Norfolk amidst fears that the returning Black soldiers and sailors would not accept their traditional social and political place.

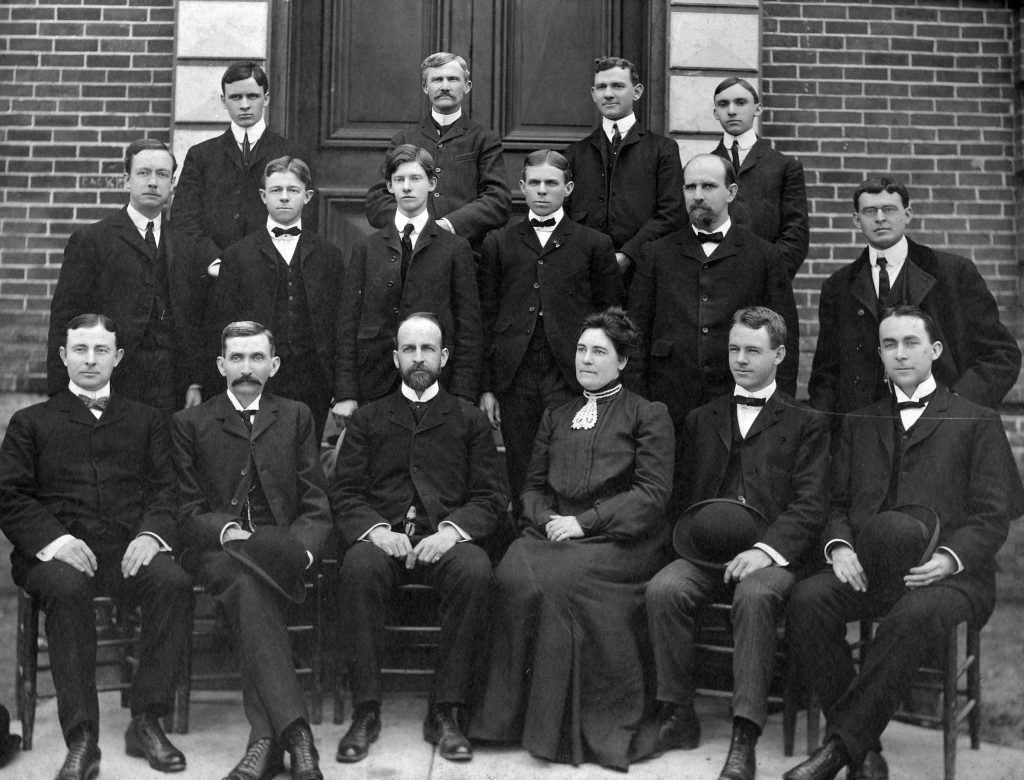

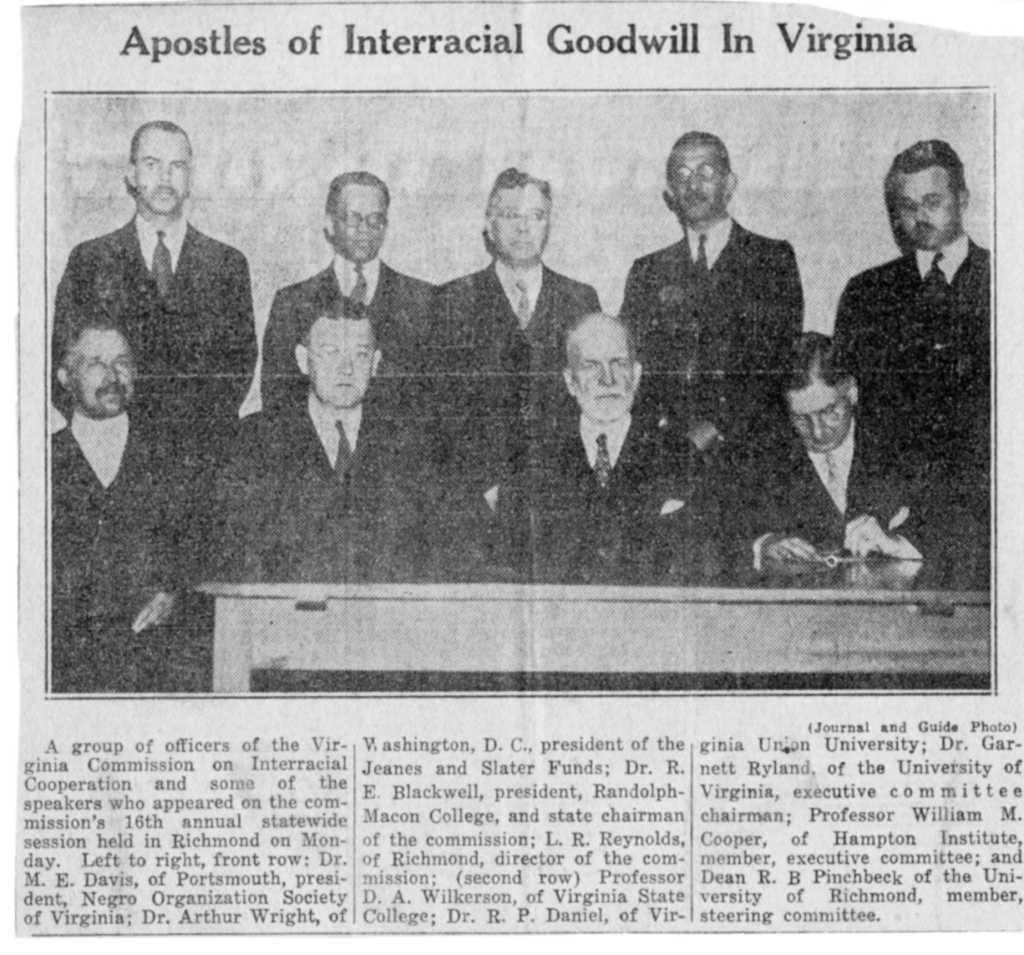

The Commission on Interracial Cooperation (CIC) was founded in 1919 as a response to the national race riots and civil unrest. Headquartered in Atlanta, the CIC sought to create communities where Blacks and Whites worked together for “bettering race relations and advancing educational and social welfare.” The organization was a decentralized association of individual state and county commissions promoting local cooperation. The Virginia Commission on Interracial Cooperation (VCIC) was comprised of educators, clergy, physicians, attorneys, newspaper editors, and business leaders from both the Black and White communities. Members of the VCIC were chosen by the White members, with the Black members having veto power over individual selections. The VCIC leadership included the presidents of many Virginia institutions of higher education, including historically Black colleges and universities. When the Virginia Commission on Interracial Cooperation was established in 1919, it selected Randolph-Macon College President Robert Emory Blackwell as its Chairman, a position he held for the following two decades.

VCIC and Randolph-Macon College

The VCIC was funded by private foundations and church organizations to support the priorities of the abolition of lynching and improving schools, health facilities, and living conditions for Blacks. While the VCIC promoted joint educational and cultural programs, the goals of the commission were limited in scope and vision. The VCIC leadership sincerely strove to improve economic conditions and social justice for Blacks, but it did not directly confront issues of segregation and the absence of social and political equality.

As Chairman of the VCIC, Blackwell worked with other Commission members to promote goodwill between the races and among the VCIC represented institutions. For example, the Negro Organization Society of Virginia invited Dr. Blackwell to speak at their annual meeting in Danville in 1921 and Randolph-Macon College campus was the site of the Society’s annual meeting in 1934. Blackwell served on the Board of Trustees of Hampton Institute (later Hampton University) and invited the Institute’s “Hampton Quartet” to perform at Randolph-Macon in 1932 and again in 1935.

Methodist Church and Race Relations

Blackwell’s efforts on behalf of racial cooperation extended beyond his work with the VCIC. The Methodist Episcopal Church (MEC) also struggled with the national problems regarding race relations, having split over the issue of slavery in 1844. The MEC was comprised primarily of northern congregations but also included some Black congregations from both the south and the north. With the creation of the all-white Methodist Episcopal Church, South (MECS), most southern Black congregations were eventually assembled into the Colored Methodist Episcopal Church (CME). These various Methodist denominations formed a Joint Commission on Unification in 1916 to try to reunite the Methodist Church. Robert Blackwell was appointed as a representative of the MECS to the Joint Commission, a cause he championed until his death.

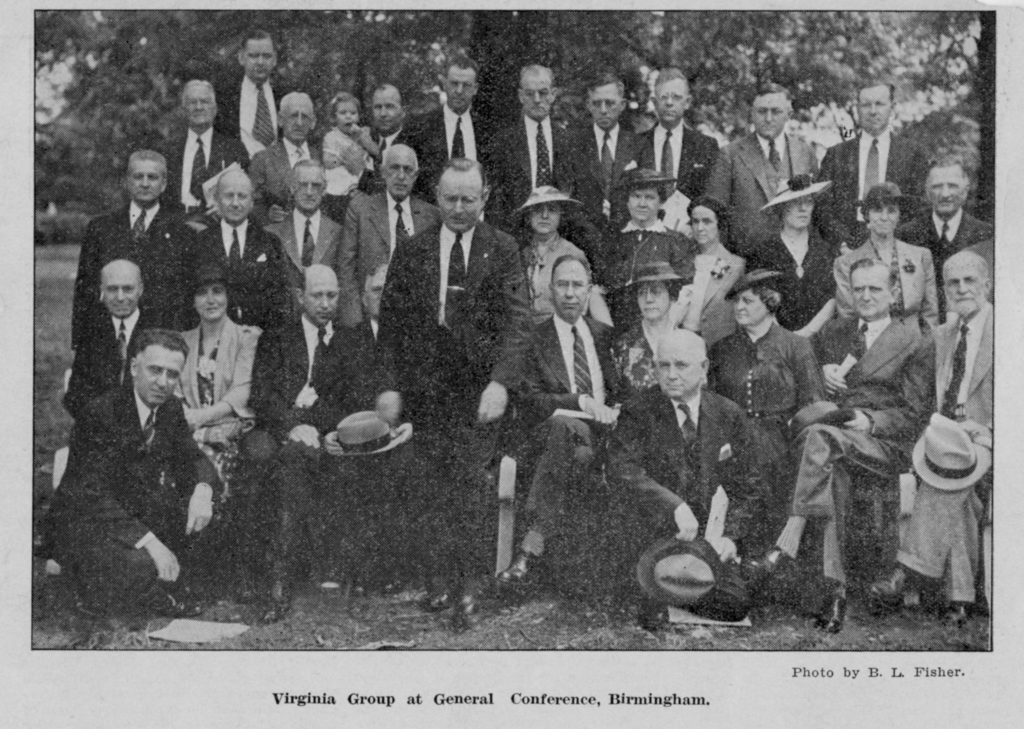

The issues confronting the Methodist Church—integration vs segregation and social equality between Black and White members—were like those facing the VCIC. The social and political status of the Black Methodists in the South was a perennial sticking point. The compromise which allowed Methodist “unification” to move forward created a racially segregated “Central Jurisdiction” for Black congregations. Blackwell was a delegate to the 1938 MECS General Conference in Birmingham when the unification plan was presented. As one of the more moderate members of the MECS delegation, Blackwell voted in favor of the unification compromise which passed by an overwhelming majority. After becoming ill while at the MECS conference in Birmingham, Blackwell went to his daughter’s home in Atlanta to recuperate. His health steadily declined, however, and he died in Atlanta on July 7, 1938.

Blackwell and other leaders of the VCIC were considered “progressive” and even “liberal” by the standards of the time. Blackwell advocated for just and civil relations between Blacks and Whites—especially the relationships between the College and its African American employees and the Ashland community—but within a racially segregated society. Ironically, Blackwell’s funeral on July 15, 1938, was likely the first significant College occasion which included a racially integrated audience. More than twenty members of the Virginia Commission on Interracial Cooperation, both Black and White, attended the funeral in the College Chapel, including Gordon B. Hancock of Virginia Union University, Dr. Robert R. Moton of Tuskegee Institute, Janie Porter Barrett of the Virginia Industrial School, and John M. Gandy of Virginia State College.

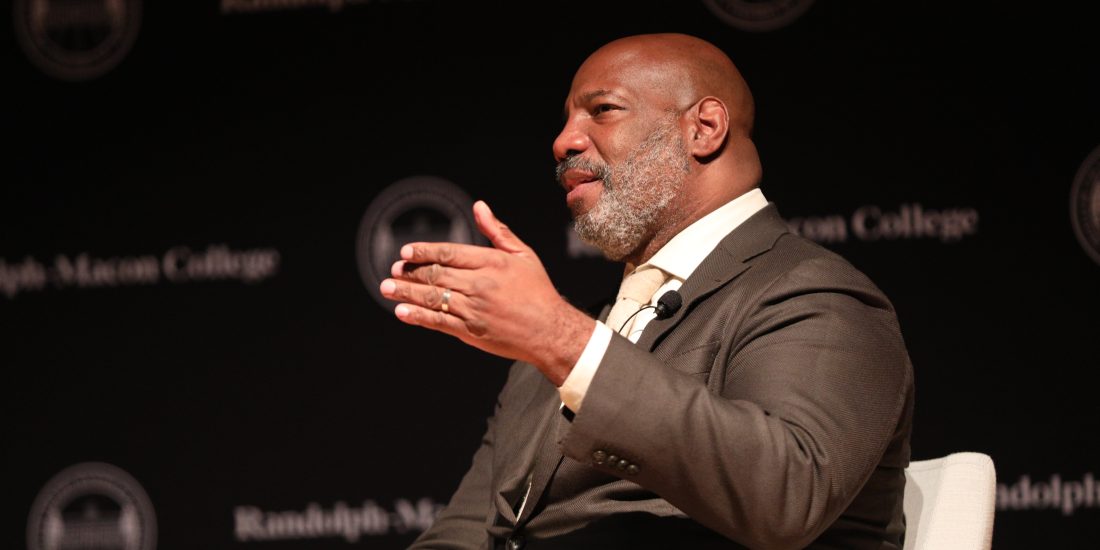

Robert E. Blackwell worked tirelessly for interracial goodwill for decades, within the Virginia Commission on Interracial Cooperation, within the Methodist Church, and within Randolph-Macon College. It would be another thirty years after Blackwell’s death, however, before Randolph-Macon graduated its first Black student, Haywood A. Payne, Class of 1968.