What I Wish I Had Known About Academic Research

Professor Lauren C. Bell, Dean of Academic Affairs and Professor of Political Science shared the following advice with the 2021 Schapiro Undergraduate Research Fellowship (SURF) students as they began their summer research, with the mentorship and guidance of faculty sponsors.

There are many things I wish someone had told me about research before I had to do it. My first introduction to real research was as an undergraduate student at the College of Wooster, which has a three-semester independent study guided research requirement for all its students. Although I had a wonderful faculty research advisor, who guided me through my research on the voting behavior of Supreme Court justices, he didn’t spend a lot of time talking with me about what to expect from research – any research.

So, here are five things I wish someone had told me about research. I hope that one or more of these might serve you well this summer, or in your future research endeavors.

1. Where you think you’re headed…maybe isn’t at all.

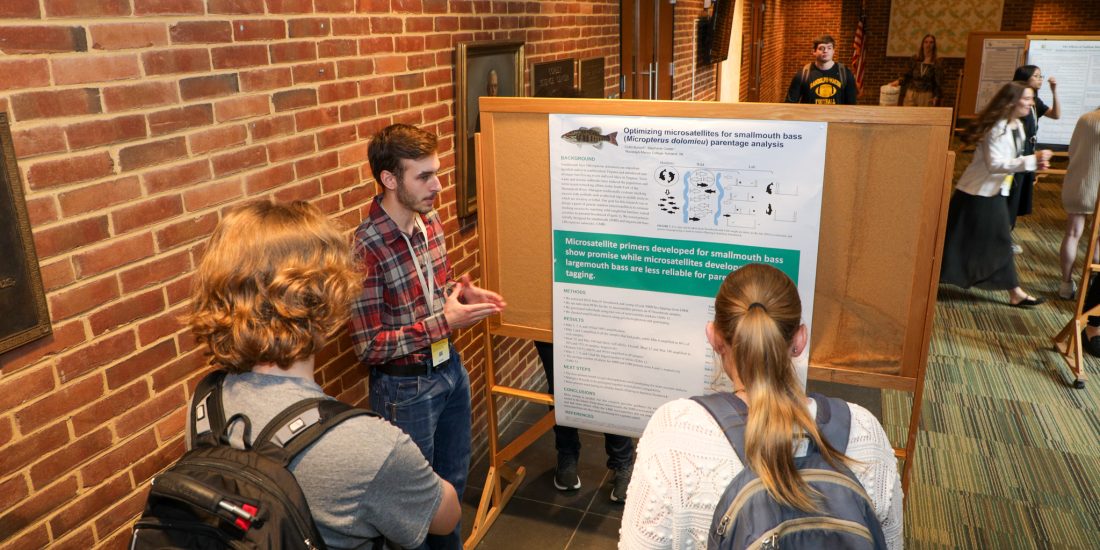

The first thing I think you should know is that where you think you’re headed maybe isn’t where you’ll end up. If I could give each summer research student an assignment, it would be to write down what you say you’re doing on Day #1 and compare it with what you present at the SURF Presentation Day in early August. I suspect that many of you will end up in a very different place than where you think you will.

This is normal.

Ask any faculty member, and we’ll tell you about all the times our research went differently from what we expected. My own doctoral dissertation about the U.S. Senate’s confirmation process for federal judges, cabinet secretaries, and ambassadors ended up being very different from what I had intended, because it turned out that data I thought would be available simply didn’t exist. But because those data had never been collected before, my project became much more important than my original, planned project ever would have been.

The important thing is that when you encounter challenges – whether it is with obtaining supplies, or accessing data, or running your analysis, or writing up your work – don’t give up. Even when things don’t go as planned, where you end up may still be a pretty great place.

2. “Creating new knowledge is hard”

“Creating new knowledge is hard.” I’ve put that statement in quotation marks, because it’s actually something a former political science research methods student, said to me about ten years ago, and it’s an observation I just love. Creating new knowledge is hard.

Perhaps you haven’t thought about your research project in that way, but at the most fundamental level, what you are doing this summer – what we all do when we engage in research – is creating new knowledge. We don’t do this out of whole cloth – we rely and build upon the work that others before us have done – but at a fundamental level, pure, academic research seeks the creation of new knowledge that leads to scientific breakthroughs, artistic expression, community building, environmental awareness, more just prosecutions, increased democracy, and a better understanding of the world around us—among countless other things. These are complicated phenomena, and creating new knowledge about them is, and should be, hard.

3. A null finding is still a finding

Related to this, sometimes for all our hard work, the relationships we set out to test turn out not to be statistically significant. Or we can’t find what we’re looking for in the archival record. Or the creation of a new work of art or music or short story simply doesn’t resonate with an audience. It can be easy to fall into the trap of thinking that all our hard work was for nothing. But in the language of hypothesis testing, a null finding is still a finding. Learning that independent variable A has no effect on dependent variable B is still new knowledge. Discovering that an archive that held a lot of promise for solving a historical puzzle is a bust still moves us forward because it narrows our search for the needed information. Hearing from a critic that our creative works need improvement helps us to know what didn’t work so that we can revise and do better next time.

4. It’s OK to ask for help

Now, of course, you’re not alone in your research endeavors this summer. You each have a research advisor – one of RMC’s tremendously impressive faculty members—who will be helping to guide you through all of the ups and downs I’ve mentioned so far. Each of these faculty members has committed to you because they believe in the value of research, they are excited to share their academic passions, and they are ready to support you to discover yours. Take advantage of these incredibly gifted mentors. Ask questions. Ask for help.

Your faculty mentors aren’t the only people you should engage with. Engage with each other. Talk to one another about your projects, including about the challenges you’re confronting. Use the incredible expertise of our librarians. And cast a wide net: you’re surrounded by talented peers and faculty from an enormous swath of disciplines at RMC this summer. I know that I have personally benefited over the years from talking with colleagues in fields as diverse as economics, music, communication studies, and sociology, who have helped me to solve problems with data analysis, theory building, and ensuring that my writing can be understood by people who don’t study what I do. Don’t assume that the only person who can help with your project is someone studying something very close to what you’re studying.

One last point about asking for help: whether it’s because you are the only person who studies what you do, or because you aren’t ready to share data that you’ve painstakingly collected, research can sometimes feel isolating, especially when those setbacks I’ve mentioned occur. So I encourage you to help to build a supportive community of SURF students and faculty this summer. Don’t only ask for help, but offer it to others as well.

5. Trust the process

Finally, trust the process. Whether your project runs exactly the way you planned it to back in March, when you submitted your proposal, or whether you spend the summer troubleshooting problems you never anticipated, you will learn many important things from this experience. You will create new knowledge—whether new to you, or new to the world. You’ll learn important lessons about the research process and the importance of mentors and peers to support you along the way. New doors will open as a result of your hard work – whether it’s the opportunity to present your work at a professional meeting, or even to publish it, or whether it’s the chance to continue your work next summer, or in graduate school, armed with the lessons you learned this summer.

Conclusion

In summary, things may not always go as planned. Where you end up in August may not be anywhere close to where you thought you would. The work will often be hard, and the outcomes may not be what you expect. But if you trust the process, accept that you’ll be both challenged and supported, and seek and offer support yourself, I think you will find that where you end up will exceed your expectations.