Tireless Dreams

Paul Sekyere-Nyantakyi ’93 went from driving a cab just to survive, to leading a laboratory that’s raising healthcare standards across his native Ghana.

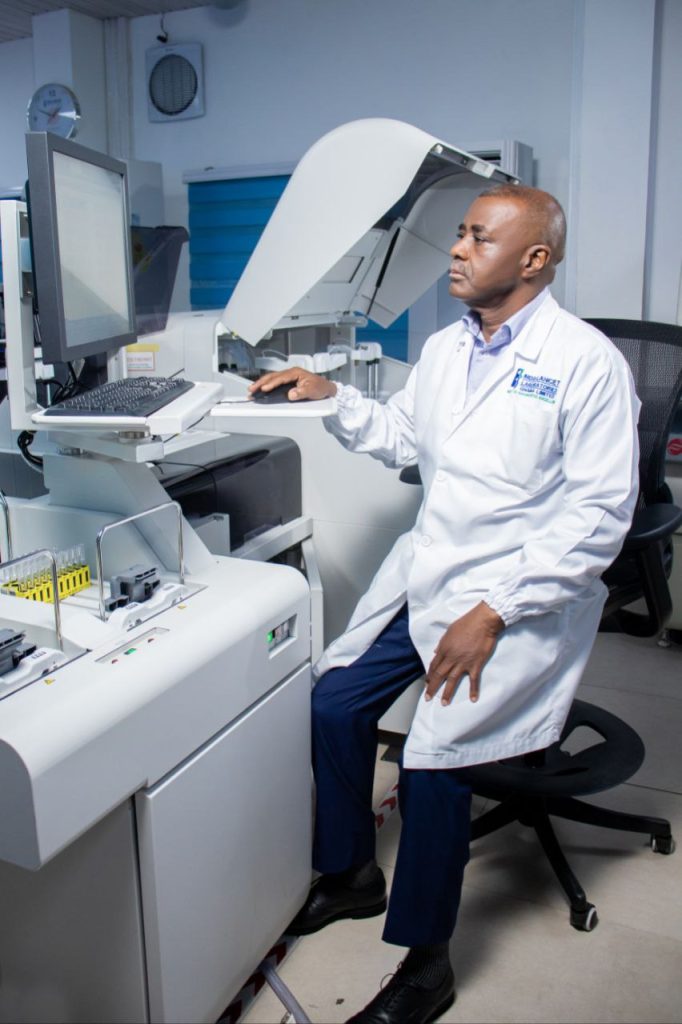

Paul Sekyere-Nyantakyi ’93 is a very focused man. It’s an appropriate demeanor for somebody who spends their days surrounded by laboratory equipment designed for accurate results. While he now serves as the CEO of MDS-Lancet Laboratories in Ghana’s capital city of Accra, his journey to that point required every bit of his focus and resolve.

His parents had no formal education themselves, but they raised eight educated children; his siblings went on to be teachers, bankers, and engineers. But Paul always wanted to be a doctor.

His mother was often sick when he was a child, and he’d promise her that one day he would become a doctor and take care of her. When both his parents died young—when Paul was just a teenager—his goal was solidified: to prevent others from feeling that pain.

Paul arrived in the United States in the 1980s with an acceptance to a college in Arkansas, expecting his work ethic to guide him through the opportunity to work and go to school. But the financial and logistical reality of his new life as an immigrant was far different than the dreams and plans he had made. He was unable to even make it to Arkansas, instead staying with a friend and settling in the northern Virginia suburbs of Washington, D.C.

“I needed to just accept and adjust to the new environment, which means I started working,” Paul recalled.

Often putting in 16 hours a day, he worked any job he could get. He washed dishes at TGI Friday’s. He was a porter in an apartment building. He delivered newspapers in the morning. Eventually, he “graduated” to driving a taxi for Alexandria Yellow Cab.

But even through years of grinding, he held on to the goal of pursuing education. A six-month computer programming course led to a job at a health insurance company in Arlington, assisting with patient intake. It would have been easy to settle, having finally secured a quality job. But his original goal had always been on his mind and he started perusing the College Board’s handbook of colleges. One school stood out for its ability to be a scientist while remaining a well-rounded student: Randolph-Macon College.

Paul drove to the Randolph-Macon College campus in Ashland, Virginia. He presented his transcripts from the computer school in Arlington, along with the results of his SAT. After undergoing a rigorous admissions committee interview, he was admitted into the Randolph-Macon Honors program, which promised full tuition coverage if a student maintained at least a 3.5 GPA.

A biology major on a pre-med track, and determined to finish his degree in three years, Paul set out on a challenging path filled with long days in the classroom and lab, taking 18 credit hours per semester and keeping his grades high.

Of course, there was still the question of how to pay for expenses beyond tuition. So, Paul did what he’s always done: he got to work. On Friday nights, he would drive back up to D.C. and drive his cab throughout the weekend, working on homework in parking lots while waiting for calls.

He credits the RMC faculty for supporting him through a successful—albeit jam-packed—academic career in Ashland. Professor Wallace Martin was the head of the biology department and was an advisor and mentor to Paul. He also describes his relationship with Professor Art Conway as “like a father and son.” Working with Dr. Conway in his lab, Paul contributed to the publication of an abstract and presented the work at the Virginia Academy of Science. Paul looked to Dr. Serge Schreiner, then a newly minted chemistry professor who’d emigrated from Luxembourg, as a friend and mentor as he navigated the challenges of assimilating to America from another nation.

As he neared graduation, Paul applied to medical schools, although he was careful to limit his search to schools that would waive his application fees. He was accepted to all of them. With his pick of elite schools like Harvard and the University of Virginia, he ultimately attended Johns Hopkins. Later, he completed an internship at Yale Medical School.

At this point, Paul’s hard work had paid off. A path to prosperity as a doctor of internal medicine in the United States was laid out before him. But he knew that he couldn’t turn back on the principles that drove him to become a doctor in the first place, and a trip back to Ghana in 1997 had opened his eyes to a more profound purpose.

“I realized that in the U.S. back then, we were in the era of evidence-based medicine, which means a lot depends on modern diagnostics,” Paul explained. “But when I came back to Ghana, the lab was abysmal.”

Recognizing a crucial need for accurate and reliable test results in Ghana—and to honor the memory of his parents and the values they instilled in him—Paul created Quest Medical Center (which eventually became Quest Medical Imaging), a modern diagnostic lab located in Accra.

Quest Medical Imaging grew, but Paul would still have to refer patients to facilities outside the country for procedures. In 2008, South African company Lancet Laboratories partnered with Paul to create MDS-Lancet Laboratories and bring truly first-class diagnostics to Ghana.

Previously, there were no facilities in the country capable of a Doppler ultrasound that could detect blood clots and prevent pulmonary embolisms. Patients would often die waiting for a diagnosis and only the wealthy could manage traveling internationally for treatment.

Today, Quest Medical Imaging and MDS-Lancet Laboratories together process over 4,000 patient samples daily with a dedicated team of more than 400 staff members and state-of-the-art technology. With locations across the country, Paul has led an effort that has completely redefined medical laboratory and radiological services in Ghana.

“I have funny philosophies. I’m here and I’m receiving free air from God. When I don’t pay my electricity, they cut it off. But somehow God is not cutting my air off,” Paul reflected, emphasizing his motivation for doing this work. “God doesn’t need anything from me apart from helping my fellow human being.”

He also holds significant gratitude to the people who impacted his life at RMC for the role they played in his journey. He recalls a close and special relationship with a number of other members of the faculty and staff, including those who helped pay for his books during his academic career like history professor James Scanlon and Rob ‘69 and Barclay DuPriest, the RMC Campus Store Manager, as well as biology professor Pat Dementi, who often sent him money to help with expenses in medical school.

In 2014, RMC awarded him an honorary Doctor of Science degree at its Commencement ceremony. “I always thank Randolph-Macon for the opportunity; they were the ones who believed in me,” Paul said. “Otherwise, the dream would have been dead.”

Never one to be satisfied, Paul has his eyes set on the next project, one that’s reminiscent of his time in the labs at RMC: setting up the nation’s first central lab for clinical trials. Until then, he continues to honor the promise of the young boy with a sick mother, providing quality medical care to the people of Ghana.

“Every patient I encounter, I look to them through the eyes of taking care of my parents,” Paul said.

This story originally appeared in the Randolph-Macon Today magazine.