Black History Month Feature: Berkleytown, A Black Community on the National Register of Historic Places

Berkleytown, a historically African American community, stands on the northern edge of Randolph-Macon’s campus. This community, which was outside the boundaries of Ashland at the time, developed at the edge of the RMC campus in the early 1900s in response to the Jim Crow era segregation ordinance passed by Ashland in 1911. In 2022, it was added to the Virginia Landmarks Register and the National Register of Historic Places in 2022 as the Berkleytown Historic District.

Berkleytown’s history is central to Black history in the region and historically important in Randolph-Macon’s history as well.

Berkleytown grew to cover approximately 60 acres, bordered by Archie Cannon Drive to the north, U.S. Route 1 to the east, Smith Street to the south, and Center Street and the railroad tracks to the west. It included homes, numerous businesses, and the heart and soul of any community, a school: first, the Hanover County Training School, which was later replaced by John M. Gandy High School.

The proximity of this community to the RMC campus meant that many residents of Berkleytown, and many of the people who had attended school in Berkleytown prior to desegregation, worked for the College, primarily in staff roles. Perhaps the most well-known is Lester Jackson, a Berkleytown resident and Hanover County Training School graduate, who worked in the RMC cafeteria for four decades, working his way up to cafeteria manager before his retirement.

Schools in Berkelytown

The Hanover County Training School was a collection of buildings designated for the education of Black students in the early 20th century and was the only school for Black children in Hanover County that included high school grades. After additional schools for Black students were built in Ashland, the school’s function transitioned to a high school.

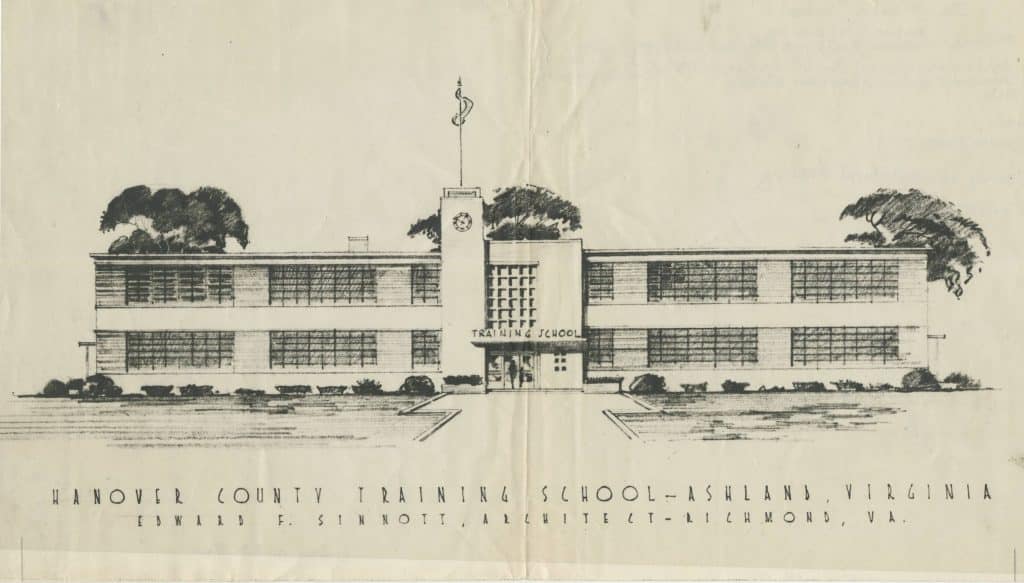

A new school building, designed by Richmond architect Edward F. Sinnott, Sr., was still referred to by its original name during its planning and construction, with the name “Training School” appearing in the architect’s drawing. The school, opened in 1950, was ultimately named John M. Gandy High School after prominent black educator Dr. John Manuel Gandy, president from 1914-1942 of the historically-black college/university now known as Virginia State University. The Gandy school was a significant improvement over the earlier school, including a heating system, indoor bathrooms, and many other modern conveniences previously denied to African American students in the area.

When the Ashland schools were integrated, Gandy became an elementary school, and when a new John M. Gandy Elementary School replaced it, the original Gandy building was converted to offices for the Hanover County Public Schools.

Stories from Berkley Town

Several interviews in the McGraw-Page Library’s “One Ashland, Many Voices” oral history project, consisting of interviews with Ashland residents conducted primarily by RMC students in 2008, discuss Berkleytown, the Gandy school, and the Berkleytown community’s interaction with its neighbor, Randolph-Macon College. Many of these interviews are available on the project’s YouTube page.

“In this community here, it was considered the upper-middle class blacks,” said Berkleytown resident, business owner, and pastor Robert Burruss. “Most of the people that lived in this community either had businesses or they were schoolteachers…and they were pretty well-educated.”

“During my time as a young person coming up with Randolph-Macon College, it was at a distance from me because it was segregated. It offered jobs. It offered support for a lot of people around here. Some of my family worked there. But it often bothered me that we could work, but we could not attend,” Burruss continued. “My daughter [Toni Burruss ‘85] attended and graduated from the College, which was a great milestone for this family because we often stood on the outside looking in, and now we had the opportunity to go in and look out.”

One of just 10 Black students out of a student body of 900, Toni Burruss adjusted to life at the College through the support of staff members who were part of her community in Berkleytown.

“Most of the employees that were here were either my family members or they were neighbors,” Toni Burruss recalled. “We were truly a minority here, trying to assimilate and fit in, trying to go to class and still dealing with some attitudes and behaviors in class…but you know, I was well taken care of while I was there because of the employees, because they knew my family.”

Jackson, the cafeteria manager, facilitated employment at the College for Berkleytown residents, including Toni Burruss’s first job putting salad in bowls as a teenager to earn spending money.

“Mr. Lester Jackson…he was a good man,” recalled Floyd Dabney, Jr., a Berkleytown resident who operated the Henry W. Dabney Funeral Home. “He would try to get kids who turned 15 to get their worker’s permit. ‘Go see Lester, see if you can get a job at the College!’ Then he would find you a job if you wanted to work.”

For More Information

The residents of Berkleytown and those who attended the schools within its borders have had a significant impact on RMC, Ashland, and beyond for over 100 years, and the importance of this historic community is now being recognized and honored as it deserves. For additional information, contact the Hanover County Black Heritage Society, the Ashland Museum, or RMC’s Flavia Reed Owen Special Collections & Archives and please join us on Feb. 16 from 4-5 p.m. in the McGraw-Page Library’s Abernathy Room, the 24/7 space, for the program “Black Heritage in Hanover” to learn more about the Black experience in Hanover County with Carolyn Hemphill from the Hanover County Black Heritage Society.

Additional research contributed by Unity Bowling and Lynda Wright